|

|

|

Архитектура Астрономия Аудит Биология Ботаника Бухгалтерский учёт Войное дело Генетика География Геология Дизайн Искусство История Кино Кулинария Культура Литература Математика Медицина Металлургия Мифология Музыка Психология Религия Спорт Строительство Техника Транспорт Туризм Усадьба Физика Фотография Химия Экология Электричество Электроника Энергетика |

THE NEGOTIATING PROCESS: DIPLOMATIC STYLES

One of the interesting problems facing students of diplomacy is to describe and explain the different styles of diplomatic bargaining among governments.21 In diplomatic negotiations, for example, do Russians evince certain bargaining styles that are unique or significantly different from those of, let us say, the English? Many retired diplomats claim in their memoirs that certain countries or societies do have distinguishable diplomatic styles. Sir Harold Nicolson, a renowned British diplomat, argued on the basis of his long experience that the bargaining styles of a country's diplomats reflect major cultural values in < their society.22 He contrasted the "shopkeeper" style of British diplomats—one that is generally pragmatic and based on the assumption that compromise is the only possible reason for and outcome of bargaining—with the style of the totalitarian governments, particularly Soviet Russia in the 1920s and during the height of the cold war, and Nazi Germany in the 1930s. The diplomats of these regimes were known for rigidity in bargaining positions; extensive use of diplomatic forums for propaganda displays; coarseness of language; a strategy of trying to wear down opponents by harangues; interminable wrangling over minute procedural points; constant repetition of slogans and cliches; and, most important, the view that agreements were tactical maneuvers only, to be broken or violated whenever it was to one's advantage (to quote Lenin, "Agreements -are like pie crusts: They are made to be broken."). Duplicity and deception were also common to diplomatic styles of the totalitarian regimes. Without the slightest qualm, the Nazi government could stage an incident that it then used to justify military action as a "reprisal" against a neighbor. Or the Soviet foreign 21 Portions of this section are reproduced from KJ. Holsti, "The Study of Diplomacy," in World Politics, eds. Gavin Boyd, James N. Rosenau, and Kenneth Thompson (New York: Free Press, 1976). Copyright © 1976, The Free Press, a Division of Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc. Reprinted by permission of The Free Press. 22 Harold Nicolson, Diplomacy, 3rd ed. (London: Oxford University Press, 1964). 186 The Instruments of Policy: Diplomatic Bargaining minister could tell President Kennedy in 1962 that the Russian missiles being placed in Cuba were only "defensive," when in fact they were capable of reaching almost any target in the United States. From these and many other examples, as well as Nicolson's analysis, we might be tempted to infer that the critical variable explaining differences in diplomatic styles is the degree to which a state is "open" or "closed." Undoubtedly, the ethical principles or cultural values expressed in "shopkeeper" diplomatic style are significantly different from those of the totalitarian style. British, French, and American diplomats were genuinely shocked at the standards of diplomatic conduct they faced among their opponents in the 1930s and during the height of the cold war. Yet, many western diplomats are biased in the direction of emphasizing the sins of revolutionary regimes (which are unorthodox largely because they do not accept the legitimacy of the international system or its norms or of their adversaries in negotiations), while forgetting their own lapses. From what we know of bureaucratic and revolutionary politics in totalitarian regimes, and assuming that diplomatic styles reflect those politics as well as general cultural values, it is probably valid to argue that the modal behavior of Soviet and Nazi diplomats was indeed rigid, blustering, coarse, filled with invective, and, above all, untrustworthy. Any tactic to wear down opponents was considered legitimate—including, in some instances, threats against the lives of diplomats themselves. However, the long history of Communist-Western negotiations shows that when it was in their interest to do so, the Soviets, Chinese, and even the Nazis have bargained straightforwardly and have kept agreements.23 That they were hard bargainers is less relevant. On the other hand, Western diplomatic styles, reflecting "open" societies, have often lapsed from their own modal characteristics as listed by Nicolson and others. President Kennedy complained of Gromyko's duplicity on the missile issue in Cuba; yet, only one year earlier, the American ambassador to the United Nations had told the world that the Bay of Pigs invasion was organized by a few segments of the Cuban army defecting from the Castro regime. He did not indicate that the enterprise had been planned, organized, financed, and directed by the Central Intelligence Agency. The diplomacy of the United States during the Vietnam War was not noted for its candor; and, even in disarmament negotiations, Americans have been known to break one of the fundamental rules of bargaining: Once you have made a concession, you cannot retract it. The British, for their part, have no less frequently broken promises, violated ' legal principles, engaged in deceit, and blocked progress in negotiations. It would not be an exaggeration to claim, nevertheless, that whatever their bargaining tactics, British diplomats always maintain verbal decorum. 23 See Lall,How Communist China Negotiates. One empirical studyof Soviet bargaining behavior establishes that when the Russians want an agreement, their diplomatic style is largely devoid of propaganda, rigidity, and other "sins." See Christer Jonsson,Soviet Bargaining Behavior: The Nuclear Test Ban Case (New York: Columbia University Press, 1979). 187 The Instruments of Policy: Diplomatic Bargaining Some important differences in diplomatic styles appear between "open" and totalitarian states, but the differences are most notable only when the "closed" states are undertaking highly expansionist policies or when they are largely isolated from contacts with the rest of the international system. As their goals become more pragmatic and inner-directed—toward meeting domestic welfare and economic needs, for example—their diplomatic styles tend toward the conventional. The "open" states, or at least the traditional Western major powers, generally adhere to a highly pragmatic style, where the major purpose of bargaining is to reach agreements rather than to emphasize side effects such as propaganda or intelligence work. But the style probably derives more from broad cultural and historical conditions than from the fact that they have democratic political systems. It would be difficult to argue, for example, that Brazilian diplomatic style (representing a relatively "closed" state) is significantly different from that of Belgium. In brief, the "open"-"closed" dichotomy may help to explain some differences in diplomatic styles, but by no means all. The nature of a state's external objectives, its position in the international system, and bureaucratic traditions are probably of equal importance. What of size? Although some foreign-policy problems of small states may differ from those of their larger neighbors, there is little reason to believe that the size factor alone can significantly influence the outlooks and styles displayed by diplomats in bargaining or problem-solving situations. The differences between British and New Zealand, or French and Finnish diplomatic styles—if there are any—can probably be explained more convincingly in terms of cultural traits, historical traditions, or the general diplomatic situation they find themselves in, than of size. Does the level of development influence diplomatic styles? The answer would be yes—at least, indirectly. Many of the developing states are also new states, often in positions of great economic dependence and holding a not entirely unjustified opinion that, in most of their relationships, they can bargain only from a position of extreme weakness. Most of these states do not have long diplomatic traditions, and few have extensive foreign-affairs bureaucracies with years of experience. Henry Kissinger has argued that whereas the developed countries suffer from the inertia of overadministration, the developing areas often lack • even the rudiments of effective bureaucracy. Where the advanced countries may drown in 'facts,' the emerging nations are frequently without the most elementary knowledge needed for forming a meaningful judgment or for implementing it once it has been taken.24 Although Kissinger may be exaggerating differences—certainly, his comments would not apply to countries such as India or Egypt—his subsequent discussion 513. 1 Henry Kissinger, "Domestic Structure and Foreign Policy," Daedalus, 95 (Spring 1966), 188 The Instruments of Policy: Diplomatic Bargaining of American diplomatic style does underline differences in foreign-policy behavior from the small developing states, particularly the more "revolutionary" ones. Whereas the developed states tend to be problem-oriented and react to situations as they arise, "charismatic-revolutionary" leaders want to create entirely new international environments and tend to develop fairly well thought-out sets of long-range objectives. Construction of "new orders" rather than piecemeal manipulation of problems is their main characteristic.25 We would expect in these circumstances that the diplomacy of the more radical developing states (Indonesia under Sukarno, Iran under Khomeiny, Guinea under Toure, and Libya under Qaddafi) would be distinct, particularly emphasizing moralistic rhetoric and the evils of the world (primarily imperialism) of which they are the main victims. Instead of problem solving based on laborious and unexciting accumulation of data, this form of diplomacy would be more comfortable in a setting where great debates and propaganda are appropriate. The reader may wish to consult some of the speeches before the United Nations General Assembly to see if there are discernible differences in rhetoric between the developed states and some of the emerging nations. Certainly the evidence about foreign-policy behavior in general, as will be discussed in Chapter 12, does not indicate that developing countries operate in a manner fundamentally different from many other states. With only a few exceptions, and, unlike the totalitarian states of the 1930s and the cold war, diplomacy as an instrument of revolutionary upheaval and systematic invasion of foreign lands is not to be seen among the developing countries. Because they are weak and often poorly informed, their bargaining strategies might differ from those of more powerful states, but that is a hypothesis that has not yet been explored in research. If size, type of political system, and level of development do not explain all the variations in diplomatic bargaining styles (and often they explain none of it), what remains? Many authorities on the subject argue at least in hypothetical form that differences derive from national characteristics or, as one author has put it, diplomacy reflects "culturally-conditioned patterns of behavior and thought." This proposition has much to commend it, but it is difficult to establish with much precision. Studies on Japanese diplomacy do reveal some common characteristics or patterns, and, as suggested, a large literature on the subject portrays Soviet diplomats as frequently exhibiting unique forms of behavior.26 But there are exceptions to any generalizations, so it is difficult to establish precisely what is typical behavior and what is unique. Here are some of the common behavioral traits ofjapanese negotiators: They tend to approach discussions with an attitude emphasizing the justice or inherent "goodness" of their position, without examining the proposition that the other side might have valid 25 Ibid., pp. 522-27. 26 See Michael Blaker, Japanese International Negotiating Style (New York: Columbia University Press, 1977); and Hiroshi Kimura, "Soviet and Japanese Negotiating Behavior: The Spring 1977 Fisheries Talks," Orbis, 24 (Spring 1980), 43-68. 189 The Instruments of Policy: Diplomatic Bargaining points as well. With this view of inherent justice, the Japanese then assume that their view will prevail simply by communicating it clearly to the adversaries. Bargaining and tactical ploys, hinting of Machiavellianism, are to be avoided not only because they are repugnant to the Japanese people who admire harmony and order in their social relations, but also because they are often counterproductive. Japanese diplomatic style thus approaches bargaining with the assumption that "right is might" and that fruitful outcomes can be secured through expressions of goodwill and clearly delineating the "goodness" of a position. Japanese style is also unaggressive in the sense that diplomats do not try to shock their opponents by introducing far-fetched maximum positions. Patiently explaining one's own just cause is the way to approach diplomatic discussions. Tactics, to the extent that they might become necessary, are used only in retaliation against the adversaries' gambits. Ad hoc management of negotiations, or bending with the wind, is the typical pattern. The evidence for this characterization comes from examination of numerous case studies of Japanese diplomacy. Thus, there is some confidence in the findings. But there are also many exceptions—for example, Japanese diplomatic behavior in negotiations with enemy or defeated states during the Pacific War or Japanese commercial diplomacy in Southeast Asia during the past decade. Thus, while the characteristics listed above may be norms, they are not in evidence in certain situations and in bargaining with certain types of opponents. Similar propositions can be related to Soviet bargaining behavior. In contrast to the Japanese who avoid tactical planning, the Russians, as many have noted, are masters at developing preplanned tactics. Strategies are elaborated before meetings, and the various ploys and gambits of bargaining are systematically worked out. Use of repetition, accusation, bluffs, warnings, threats, ultimatums, innuendos, "stonewalling," and time limits—whatever tactics are most useful in wearing down opponents—are not responses to the immediate situation but the implementation of carefully orchestrated plans. Also, unlike the Japanese, the Russians have been noted for diplomatic rudeness—for example, by dictating the time and place of negotiations, cancelling sessions at the last moment, and employing intemperate language. But these characteristics also tend to be situa-tionally determined. They are frequently not displayed when the Russians are? committed to seeking an agreement or when they are bargaining with equals or superiors. Such demeanor may be more typical in situations where they are bargaining with adversaries whom they consider inferior in rank. We must close, then, with the thought that differences in bargaining style are obvious and sometimes are so pronounced as to constitute norms. But in different situations and at different times, other forms of behavior come to the fore. It should be pointed out as well that as diplomats become enmeshed in a global network of constant contacts, over a long period of time, certain rules or norms of behavior emanating from global diplomatic practice may "wash away" the diplomat's uniquely national characteristics. Moreover, as the nature of problems on the international 190 The Instruments of Policy: Diplomatic Bargaining agenda becomes increasingly complex requiring a high degree of technical competence, individual idiosyncracies, such as intelligence, knowledge, dedication, laziness, alertness, and the like, may be more important in bargaining behavior than culturally conditioned norms. SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY Acheson, Dean, Meetings at the Summit: A Study in Diplomatic Method. Durham: University of New Hampshire Press, 1958. Bell, Coral, Negotiating from Strength. London: Chatto & Windus, 1962. Blaker, Michael, Japanese International Negotiating Style. New York: Columbia University Press, 1977. Campbell, John C, "Negotiating with the Soviets: Some Lessons of the War Period," Foreign Affairs, 34 (1956), 305-19. Clark, Eric, Diplomat: The World of International Diplomacy. New York: Taplinger, 1974. Claude, Inis L., Jr., "Multilateralism: Diplomatic and Otherwise," International Organization, 12 (1958), 43-52. Craig, Gordon A., "On the Diplomatic Revolution of Our Times," The Haynes Foundation Lectures, University of California, Riverside, April 1961. --------, "Totalitarian Approaches to Diplomatic Negotiations," in Studies in Diplomatic History and Historiography in Honour ofG.P. Gooch, ed. A.O. Sarkissian. London: Longmans, Green, 1961. -, and Felix Gilbert, eds., The Diplomats: 1919-1939. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1953. Hovet, Thomas, Jr., "United Nations Diplomacy," Journal of International Affairs, 17 (1963), 29-41. Ikle, Fred C, How Nations Negotiate. New York: Harper & Row, 1964. Jensen, Lloyd, "Soviet-American Bargaining Behavior in the Postwar Disarmament Negotiations," Journal of Conflict Resolution, 7 (1963), 522-41. Jervis, Robert, The Logic of Images in International Relations. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1970. Jonsson, Christer, Soviet Bargaining Behavior: The Nuclear Test Ban Case. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979. Lall, Arthur S., How Communist China Negotiates. New York: Columbia University Press, 1968. --------, Modern International Negotiation: Principles and Practice. New York: Columbia University Press, 1966. Lauren, Paul Gordon, ed., Diplomacy: New Approaches in History, Theory, Policy. New York: The Free Press, 1979. Lockhart, Charles, Bargaining in International Conflict. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979. 191 The Instruments of Policy: Diplomatic Bargaining Nicolson, Sir Harold George, Diplomacy, 3d ed. London, New York: Oxford University Press, Inc., 1964. ---------, "Diplomacy Then and Now," Foreign Affairs, 40 (1961), 39-49. Nogee, Joseph L., "Propaganda and Negotiation: The Case of the Ten-Nation Disarmament Committee," Journal of Conflict Resolution, 7 (1963), 510-21. Regala, Roberto, Trends in Modern Diplomatic Practice. Milan: A. Giuffre, 1959. Rusk, Dean, "Parliamentary Diplomacy: Debate versus Negotiation," World Affairs Interpreter, 26 (1955), 121-38. Samelson, Louis Т., Soviet and Chinese Negotiating Behavior: The Western View^(Rey-erly Hills, Calif.: Sage Publications, 1976). Sawyer, Jack, and Harold Guetzkow, "Bargaining and Negotiation in International Relations," in International Behavior: A Social-Psychological Analysis, ed. Herbert C. Kelman. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1965. Schelling, Thomas C, The Strategy of Conflict. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1960. Snyder, Glenn H., and Paul Diesing, Conflict Among Nations: Bargaining, Decision Making, and System Structure in International Crises. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977. Spanier, John W., and Joseph L. Nogee, The Politics of Disarmament: A Study in Soviet-American Gamesmanship. New York: Praeger, 1962. Strang, William, The Diplomatic Career. London: A. Deutsch, 1962. Trevelyan, Humphrey, Diplomatic Channels. London: Macmillan, 1973. Winham, Gilbert, "International Negotiation in an Age of Transition," International Journal (Winter 1979-1980), pp. 1-20. Wood, John R., and Jean Serrs, Diplomatic Ceremonial and Protocol. New York: Columbia University Press, 1970. Zartman, I. William, The Negotiation Process: Theories and Application. Beverly Hills, Calif: Sage Publications, 1978.

The Instruments of Policy: Propaganda

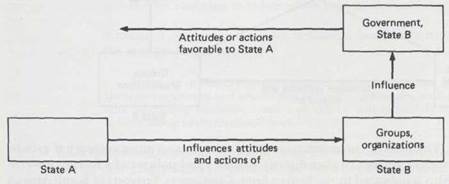

International political relationships have traditionally been conducted by government officials. Prior to the development of political democracy and modern totalitarianism, the conduct of foreign affairs was the exclusive province of royal emissaries and professional diplomats. Louis XIV's famous phrase, "I'etat, c'est moi," may seem strange to those who think of government in impersonal terms; but until the nineteenth century, the interests of any political unit were usually closely related to the personal and dynastic interests of its rulers. The wielding of influence was limited to direct contacts between those who made policy for the state. Diplomats bargained and court officials made policy decisions, but all were relatively indifferent to the public response abroad, if any, to their actions. They had to impress their foreign counterparts, not foreign populations. Communications across the boundaries of political units were in any case sporadic. Travel was limited and few people had any firsthand knowledge even of their own countrymen. In most societies, nonaristocratic people were illiterate, unknowledgeable about affairs outside their town or valley, and generally apathetic toward any political issue that did not directly concern their everyday life. The instruments of communication were so crude as to permit only a small quantity and languorous flow of information from abroad. Populations were isolated from outside influences; if a diplomat could not achieve his or her government's designs through straightforward bargaining, it would be to no avail to appeal to the foreign population, which had no decisive influence in policy making. 193 The Instruments of Policy: Propaganda With the development of mass politics—widespread involvement of the average citizen or subject in political affairs—and a widening scope of private contacts between people of different nationalities, the psychological and public opinion dimensions of foreign policy have become increasingly important. Insofar as people, combined into various social classes, movements, and interest groups, play a role in the determining of policy objectives and the means used to achieve or defend them, they themselves become a target of persuasion. Governments no longer make promises of rewards or threats of punishment just to foreign diplomats and foreign office officials; they make them to entire societies. One of the unique aspects of modern international political relationships is the deliberate attempt by governments, through diplomats and propagandists, to influence the attitudes and behavior of foreign populations, or of specific ethnic, class, religious, economic, or language groups within those populations. The officials making propaganda hope that these foreign groups or the entire population will in turn influence the attitudes and actions of their own government. To cite one illustration: During 1974, the military junta in Chile hired an American public relations firm in New York to frame programs for altering Americans' highly unfavorable "image" of that government. This action was by no means untypical; today there are more than 400 active agencies in the United States using propaganda on behalf of a foreign government.1 Most of the agencies are concerned with promoting tourism and trade, but others have a distinctly political mission: Their task is to influence certain segments of a population in hopes that these will, in turn, affect government programs. The propagandist's model of the influence process appears in the accompanying figure.

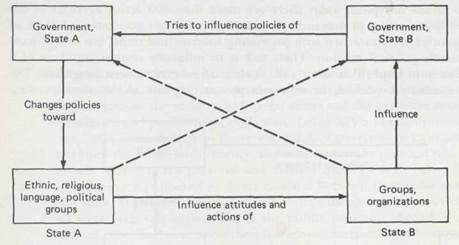

Virtually all governments conduct external information programs. All the major powers have large bureaucracies at home and officials abroad whose task it is to create favorable attitudes abroad for their own government's policies. Even the smallest states have press attaches and public relations men attached 1 W. Phillips Davison, "Some Trends in International Propaganda," in L. John Martin, ed., Propaganda in International Affairs (Philadelphia: Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 398, 1971), p. 12. 194 The Instruments of Policy: Propaganda to their embassies in major countries. Their function is to make'contacts with press officials, to send out bulletins and news sheets to all sorts of organizations and individuals that might be interested in events and conditions in the small country, and to answer myriads of questions submitted to them by prospective tourists and school children—in short, their function is to create a favorable "image" of their country abroad. In view of the extensive networks of nongovernment transactions in the world, propaganda is also conducted at unofficial levels, where a group or movement in one state seeks to alter or reinforce attitudes in another. For example, various spokesmen of black groups in South Africa have toured many countries, telling audiences of the conditions of their people at home and of the South African government's apartheid policies. They hope these audiences will somehow influence their own governments to change their policies toward South Africa and thereby promote a change in that government's policies toward the blacks. This is the case where a nonstate actor seeks to improve its condition or achieve its domestic objectives by making linkages with foreign groups or audiences. The model would appear as follows:

The flow of communication may become even more complex if groups within society attempt to alter directly attitudes and policies of a foreign government. This is indicated by the broken lines. Consumers' boycotts of South African wines are one example. Such "unofficial" lines of persuasion and propaganda are extensive in the world today, particularly as the importance of nonstate actors increases in international politics. Multinational corporations not only disseminate commercial advertising but work on governments and publics, through propaganda campaigns, to try to create a better "climate" for investment and operation. Transnational voluntary associations frequently employ information officers and staff to "tell their story" to audiences around the world. And 195 The Instruments of Policy: Propaganda terrorist groups and individuals have resorted to skyjacking, kidnapping, and seemingly senseless killings as means of publicizing their grievances throughout the world. The sudden, dramatic act can have a much greater political impact than the standard propaganda program disseminated through print or broadcasting. Although the subsequent discussion focuses on government propaganda, we should remember that a variety of nonstate actors and transnational organizations can conduct their tasks successfully only to the extent that they are able to create or sustain favorable public attitudes in many countries. International propaganda is not a monopoly of government information ministries. WHAT IS PROPAGANDA? Definitions of propaganda are as plentiful as the books and articles that have been written on the subject. Obviously, not all communication is propaganda, nor are all diplomatic exchanges undertaken to modify foreign attitudes and actions. After a careful review of various definitions, Terence Quaker suggests that propaganda is the . . . deliberate attempt by some individual or group to form, control, or alter the attitudes of other groups by the use of the instruments of communication, with the intention that in any given situation the reaction of those so influenced will be that desired by the propagandist. ... In the phrase "the deliberate attempt" lies the key to the idea of propaganda. This is the one thing that marks propaganda from non-propaganda. ... It seems clear, therefore, that any act of promotion can be propaganda only if and when it becomes part of a deliberate campaign to induce action through the control of attitudes.2 Kimball Young uses a similar definition but places more emphasis on action. He sees propaganda as . . . the more or less deliberately planned and systematic use of symbols, chiefly through suggestion and related psychological techniques, with a view to altering and controlling opinions, ideas, and values, and ultimately to changing overt actions along predetermined lines.3 Both definitions have four common elements: (1) a communicator with the intention of changing attitudes, opinions, and behavior of others; (2) the symbols— written, spoken, or behavioral—used by the communicator; (3) the media of communication; and (4) the audience, or, as it is often called in the terminology of public opinion studies, the "target." Since propaganda, according to these definitions, involves essentially 2 Terence H. Quaker, Propaganda and Psychological Warfare (New York: Random House, 1962), p. 27. 3 Quoted in J.A.C. Brown, Techniques of Persuasion: From Propaganda to Brainwashing (Middlesex, Eng.: Penguin Books, 1963), p. 19. 196 The Instruments of Policy: Propaganda a process of persuasion, it cannot be equated with scientific efforts to arrive at some truth. It is not logical discourse or dialectical investigation. It relies more on selection of facts, partial explanations, and predetermined answers. The content of propaganda is therefore seldom completely "true," but neither is it wholly false, as is so often assumed. The propagandist is concerned with maximizing persuasiveness, not with adhering to some standard of scholarship or uncovering some new fact. The common tendency to equate propaganda with falsehood may itself be a result of propaganda. Western newspaper editorials frequently brand Communist speeches or diplomatic maneuvers as "propaganda," while the activities of their own governments abroad are known as "information programs." The implication is usually quite clear: The Soviet version of reality is false, while Western versions are true. In the context of our own values, beliefs, and perceptions of reality, foreign information may indeed seem a deliberate distortion of the truth. Soviet propagandists have in many instances told deliberate lies; but from the point of view of their images of aggressive Western intentions, and from their culture and values, much of their work involves the dissemination of legitimate information. Similarly, to Soviet audiences, who are taught to think in the framework of Marxist-Leninist concepts, information sponsored by Western governments may also be seen as involving distortions of reality.

Поиск по сайту: |