|

|

|

Архитектура Астрономия Аудит Биология Ботаника Бухгалтерский учёт Войное дело Генетика География Геология Дизайн Искусство История Кино Кулинария Культура Литература Математика Медицина Металлургия Мифология Музыка Психология Религия Спорт Строительство Техника Транспорт Туризм Усадьба Физика Фотография Химия Экология Электричество Электроника Энергетика |

DENOTATIVE AND CONNOTATIVE MEANING

In the previous paragraphs we emphasised the complexity of word meaning and mentioned its possible segmentation into denotative and connotative meaning. In this paragraph we shall analyse these in greater detail. In most cases the denotative meaning is essentially cognitive: it conceptualises and classifies our experience and names for the listener some objects spoken about. Fulfilling the significative and the communicative functions of the word it is present in every word and may be regarded as the central factor in the functioning of language. The expressive function of the language with its orientation towards the speaker’s feelings, and the pragmatic function dealing with the effect of words upon listeners are rendered in connotations. Unlike the denotative meaning, connotations are optional. The description of the denotative meaning or meanings is the duty of lexicographers in unilingual explanatory dictionaries. The task is a difficult one because there is no clear-cut demarcation line between the semantic features, strictly necessary for each definition, and those that are optional. A glance at the definitions given in several dictionaries will suffice to show how much they differ in solving the problem. A cat, for example, is defined by Hornby as “a small fur-covered animal often kept as a pet in the house”. Longman in his dictionary goes into greater detail: a cat is “a small animal with soft fur and sharp teeth and claws, often kept as a pet, or in buildings to catch mice”. The Chambers Dictionary gives a scientific definition — “a cat is a carnivore of the genus Felix, esp. the domesticated kind”. The examples given above bring us to one more difficult problem. Namely, whether in analysing a meaning we should be guided by all that science knows about the referent, or whether a linguist has to formulate the simplest possible concept as used by every speaker. If so, what are the features necessary and sufficient to characterise the referent? The question was raised by many prominent scientists, the great Russian philologist A. A. Potebnya among them. A. A. Potebnya distinguished the “proximate” word meaning with the bare minimum of characteristic features as used by every speaker in everyday life, and the “distant” word meaning corresponding to what specialists know about the referent. The latter type we could have called ‘special’ or ‘terminological’ meaning. A. A. Potebnya maintained that linguistics is concerned only with the first type. The problem is by no means simple, especially for lexicographers, as is readily seen from the above lexicographic treatment of the word cat. The demarcation line between the two types is becoming more fluid; with the development of culture the gap between the elementary notions of a layman and the more and more exact concepts of a specialist narrows in some spheres and widens in others. The concepts themselves are constantly changing. The speakers’ ideolects vary due to different life experience, education and other extra-linguistic factors. The bias of studies depends upon their ultimate goals. If lexicology is needed as the basis for language teaching in engineering colleges, we have to concentrate on terminological semantics, if on the other hand it is the theory necessary for teaching English at school, the meaning with the minimum semantic components is of primary importance. So we shall have to concentrate on this in spite of all its fuzziness. Now, if the denotative meaning exists by virtue of what the word refers to, connotation is the pragmatic communicative value the word receives by virtue of where, when, how, by whom, for what purpose and in what contexts it is or may be used. Four main types of connotations are described below. They are stylistic, emotional, evaluative and expressive or intensifying. The orientation toward the subject-matter, characteristic, as we have seen, of the denotative meaning, is substituted here by pragmatic orientation toward speaker and listener; it is not so much what is spoken about as the attitude to it that matters. When associations at work concern the situation in which the word is uttered, the social circumstances (formal, familiar, etc.), the social relationships between the interlocutors (polite, rough), the type and purpose of communication (learned, poetic, official, etc.), the connotation is stylistic. An effective method of revealing connotations is the analysis of synonymic groups, where the identity of denotation meanings makes it possible to separate the connotational overtones. A classical example for showing stylistic connotations is the noun horse and its synonyms. The word horse is stylistically neutral, its synonym steed is poetic, nag is a word of slang and gee-gee is baby language. An emotional or affective connotation is acquired by the word as a result of its frequent use in contexts corresponding to emotional situations or because the referent conceptualised and named in the denotative meaning is associated with emotions. For example, the verb beseech means 'to ask eagerly and also anxiously'. E. g.: He besought a favour of the judge (Longman). Evaluative connotation expresses approval of disapproval. Making use of the same procedure of comparing elements of a synonymic group, one compares the words magic, witchcraft and sorcery, all originally denoting art and power of controlling events by occult supernatural means, we see that all three words are now used mostly figuratively, and also that magic as compared to its synonyms will have glamorous attractive connotations, while the other two, on the contrary, have rather sinister associations. It is not claimed that these four types of connotations: stylistic, emotional, evaluative and intensifying form an ideal and complete classification. Many other variants have been proposed, but the one suggested here is convenient for practical analysis and well supported by facts. It certainly is not ideal. There is some difficulty for instance in separating the binary good/bad evaluation from connotations of the so-called bias words involving ideological viewpoints. Bias words are especially characteristic of the newspaper vocabulary reflecting different ideologies and political trends in describing political life. Some authors think these connotations should be taken separately. The term bias words is based on the meaning of the noun bias ‘an inclination for or against someone or something, a prejudice’, e. g. a newspaper with a strong conservative bias. The following rather lengthy example is justified, because it gives a more or less complete picture of the phenomenon. E. Waugh in his novel “Scoop” satirises the unfairness of the Press. A special correspondent is sent by a London newspaper to report on a war in a fictitious African country Ishmalia. He asks his editor for briefing: “Can you tell me who is fighting whom in Ishmalia?” “I think it is the Patriots and the Traitors.” “Yes, but which is which?” “Oh, I don’t know that. That’s Policy, you see [...] You should have asked Lord Copper.” “I gather it’s between the Reds and the Blacks.” “Yes, but it’s not quite so easy as that. You see they are all Negroes. And the Fascists won’t be called black because of their racial pride. So they are called White after the White Russians. And the Bolshevists want to be called black because of their racial pride.” (Waugh) The example shows that connotations are not stable and vary considerably according to the ideology, culture and experience of the individual. Even apart of this satirical presentation we learn from Barn-hart’s dictionary that the word black meaning ‘a negro’, which used to be impolite and derogatory, is now upgraded by civil rights movement through the use of such slogans as “Black is Beautiful” or “Black Power”. A linguistic proof of an existing unpleasant connotation is the appearance of euphemisms. Thus backward students are now called under-achievers. Countries with a low standard of living were first called undeveloped, but euphemisms quickly lose their polite character and the unpleasant connotations are revived, and then they are replaced by new euphemisms such as less developed and then as developing countries. A fourth type of connotation that should be mentioned is the intensifying connotation (also expressive, emphatic). Thus magnificent, gorgeous, splendid, superb are all used colloquially as terms of exaggeration. We often come across words that have two or three types of connotations at once, for example the word beastly as in beastly weather or beastly cold is emotional, colloquial, expresses censure and intensity. Sometimes emotion or evaluation is expressed in the style of the utterance. The speaker may adopt an impolite tone conveying displeasure (e. g. Shut up!). A casual tone may express friendliness о r affection: Sit down, kid [...] There, there — just you sit tight (Chris tie). 4 И В Арнольд 49 Polysemy is a phenomenon of language not of speech. The sum total of many contexts in which the word is observed to occur permits the lexicographers to record cases of identical meaning and cases that differ in meaning. They are registered by lexicographers and found in dictionaries. A distinction has to be drawn between the lexical meaning of a word in speech, we shall call it contextual meaning, and the semantic structure of a word in language. Thus the semantic structure of the verb act comprises several variants: ‘do something’, ‘behave’, ‘take a part in a play’, ‘pretend’. If one examines this word in the following aphorism: Some men have acted courage who had it not; but no man can act wit (Halifax), one sees it in a definite context that particularises it and makes possible only one meaning ‘pretend’. This contextual meaning has a connotation of irony. The unusual grammatical meaning of transitivity (act is as a rule intransitive) and the lexical meaning of objects to this verb make a slight difference in the lexical meaning. As a rule the contextual meaning represents only one of the possible variants of the word but this one variant may render a complicated notion or emotion analyzable into several semes. In this case we deal not with the semantic structure of the word but with the semantic structure of one of its meanings. Polysemy does not interfere with the communicative function of the language because the situation and context cancel all the unwanted meanings. Sometimes, as, for instance in puns, the ambiguity is intended, the words are purposefully used so as to emphasise their different meanings. Consider the replica of lady Constance, whose son, Arthur Plantagenet is betrayed by treacherous allies: LYMOGES (Duke of Austria): Lady Constance, peace! In the time of Shakespeare peace as an interjection meant ‘Silence!’ But lady Constance takes up the main meaning — the antonym of war. Geoffrey Leech uses the term reflected meaning for what is communicated through associations with another sense of the same word, that is all cases when one meaning of the word forms part of the listener’s response to another meaning. G. Leech illustrates his point by the following example. Hearing in the Church Service the expression The Holy Ghost, he found his reaction conditioned by the everyday unreligious and awesome meaning ‘the shade of a dead person supposed to visit the living’. The case where reflected meaning intrudes due to suggestivity of the expression may be also illustrated by taboo words and euphemisms connected with the physiology of sex. Consider also the following joke, based on the clash of different meanings of the word expose (‘leave unprotected’, ‘put up for show’, ‘reveal the guilt of’). E. g.: Painting is the art of protecting flat surfaces from the weather and exposing them to the critic. Or, a similar case: “Why did they hang this picture?” “Perhaps, they could not find the artist.” Contextual meanings include nonce usage. Nonce words are words invented and used for a particular occasion. The study of means and ways of naming the elements of reality is called onomasiology. As worked out in some recent publications it received the name of Theory of Nomination.1 So if semasiology studies what it is the name points out, onomasiology and the theory of nomination have to show how the objects receive their names and what features are chosen to represent them. Originally the nucleus of the theory concerned names for objects, and first of all concrete nouns. Later on a discussion began, whether actions, properties, emotions and so on should be included as well. The question was answered affirmatively as there is no substantial difference in the reflection in our mind of things and their properties or different events. Everything that can be named or expressed verbally is considered in the theory of nomination. Vocabulary constitutes the central problem but syntax, morphology and phonology also have their share. The theory of nomination takes into account that the same referent may receive various names according to the information required at the moment by the process of communication, e. g. Walter Scott and the author of Waverley (to use an example known to many generations of linguists). According to the theory of nomination every name has its primary function for which it was created (primary or direct nomination), and an indirect or secondary function corresponding to all types of figurative, extended or special meanings (see p. 53). The aspect of theory of nomination that has no counterpart in semasiology is the study of repeated nomination in the same text, as, for instance, when Ophelia is called by various characters of the tragedy: fair Ophelia, sweet maid, dear maid, nymph, kind sister, rose of May, poor Ophelia, lady, sweet lady, pretty lady, and so on. To sum up this discussion of the semantic structure of a word, we return to its definition as a structured set of interrelated lexical variants with different denotational and sometimes also connotational meanings. These variants belong to the same set because they are expressed by the same combination of morphemes, although in different contextual conditions. The elements are interrelated due to the existence of some common semantic component. In other words, the word’s semantic structure is an organised whole comprised by recurrent meanings and shades of meaning that a particular sound complex can assume in different contexts, together with emotional, stylistic and other connotations, if any. Every meaning is thus characterised according to the function, significative or pragmatic effect that it has to fulfil as denotative and connotative meaning referring the word to the extra-linguistic reality and to the speaker, and also with respect to other meanings with which it is contrasted. The hierarchy of lexico-grammatical variants and shades of meaning within the semantic structure of a word is studied with the help of formulas establishing semantic distance between them developed by N. A. Shehtman and other authors.

CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS The contextual method of linguistic research holds its own alongside statistical, structural and other developments. Like structural methods and procedures, it is based on the assumption that difference in meaning of linguistic units is always indicated by a difference in environment. Unlike structural distributional procedures (see §5.2, 5.3) it is not formalised. In some respects, nevertheless, it is more rigorous than the structural procedures, because it strictly limits its observations and conclusions to an impressive corpus of actually recorded material. No changes, whether controlled or not, are permitted in linguistic data observed, no conclusions are made unless there is a sufficient number of examples to support their validity. The size of a representative sample is determined not so much by calculation though, but rather by custom. Words are observed in real texts, not on the basis of dictionaries. The importance of the approach cannot be overestimated; in fact, as E. Nida puts it, “it is from linguistic contexts that the meanings of a high proportion of lexical units in active or passive vocabularies are learned."1 The notion of context has several interpretations. According to N. N. Amosova context is a combination of an indicator or indicating minimum and the dependant, that is the word, the meaning of which is to be rendered in a given utterance. The results until recently were, however more like a large collection of neatly organised examples, supplemented with comments. A theoretical approach to this aspect of linguistics will be found in the works by G. V. Kolshansky. Contextual analysis concentrated its attention on determining the minimal stretch of speech and the conditions necessary and sufficient to reveal in which of its individual meanings the word in question is used. In studying this interaction of the polysemantic word with the syntactic configuration and lexical environment contextual analysis is more concerned with specific features of every particular language than with language universals. Roughly, context may be subdivided into lexical, syntactical and mixed. Lexical context, for instance, determines the meaning of the word black in the following examples. Black denotes colour when used with the key-word naming some material or thing, e. g. black velvet, black gloves. When used with key-words denoting feeling or thought, it means ‘sad’, ‘dismal’, e. g. black thoughts, black despair. With nouns denoting time, the meaning is ‘unhappy’, ‘full of hardships’, e. g. black days, black period. If, on the other hand, the indicative power belongs to the syntactic pattern and not to the words which make it up, the context is called syntactic. E. g. make means ‘to cause’ when followed by a complex object: I couldn’t make him understand a word I said.

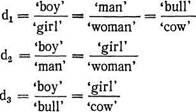

A purely syntactic context is rare. As a rule the indication comes from syntactic, lexical and sometimes morphological factors combined. Thus, late, when used predicatively, means ‘after the right, expected or fixed time’, as be late for school. When used attributively with words denoting periods of time, it means ‘towards the end of the period’, e. g. in late summer. Used attributively with proper personal nouns and preceded with a definite article, late means ‘recently dead’. All lexical contexts are subdivided into lexical contexts of the first degree and lexical contexts of the second degree. In the lexical context of the first degree there is a direct syntactical connection between the indicator and the dependent: He was arrested on a treason charge. In lexical context of the second degree there is no direct syntactical connection between a dependent and the indicator. E.g.: I move that Mr Last addresses the meeting (Waugh). The dependent move is not directly connected to the indicating minimum addresses the meeting. Alongside the context N. N. Amosova distinguishes speech situation, in which the necessary indication comes not from within the sentence but from some part of the text outside it. Speech situation with her may be of two types: text-situation and life-situation. In text-situation it is a preceding description, a description that follows or some word in the preceding text that help to understand the ambiguous word. E. Nida gives a slightly different classification. He distinguishes linguistic and practical context. By practical context he means the circumstances of communication: its stimuli, participants, their relation to one another and to circumstances and the response of the listeners. COMPONENTIAL ANALYSIS A good deal of work being published by linguists at present and dealing with semantics has to do with componential analysis.1 To illustrate what is meant by this we have taken a simple example (see p. 41) used for this purpose by many linguists. Consider the following set of words: man, woman, boy, girl, bull, cow. We can arrange them as correlations of binary oppositions man : : woman = boy : : girl = bull : : cow. The meanings of words man, boy, bull on the one hand, and woman, girl and cow, on the other, have something in common. This distinctive feature we call a semantic component or seme. In this case the semantic distinctive feature is that of sex — male or female. Another possible correlation is man : : boy = woman : : girl. The distinctive feature is that of age — adult or non-adult. If we compare this with a third correlation man : : bull = woman : : cow, we obtain a third distinctive feature contrasting human and animal beings. In addition to the notation given on p. 41, the componential formula may be also shown by brackets. The meaning of man can be described as (male (adult (human being))), woman as (female (adult (human being))), girl as (female (non-adult (human being))), etc.

Componential analysis is thus an attempt to describe the meaning of words in terms of a universal inventory of semantic components and their possible combinations.1 Componential approach to meaning has a long history in linguistics.2 L. Hjelmslev’s commutation test deals with similar relationships and may be illustrated by proportions from which the distinctive features d1, d2, d3 are obtained by means of the following procedure:

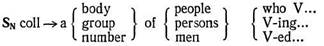

hence As the first relationship is that of male to female, the second, of young to adult, and the third, human to animal, the meaning ‘boy’ may be characterised with respect to the distinctive features d1, d2, d3 as containing the semantic elements ‘male’, ‘young’, and ‘human’. The existence of correlated oppositions proves that these elements are recognised by the vocabulary. In criticising this approach, the English linguist Prof. W. Haas3 argues that the commutation test looks very plausible if one has carefully selected examples from words entering into clear-cut semantic groups, such as terms of kinship or words denoting colours. It is less satisfactory in other cases, as there is no linguistic framework by which the semantic contrasts can be limited. The commutation test, however, borrows its restrictions from philosophy. A form of componential analysis describing semantic components in terms of categories represented as a hierarchic structure so that each subsequent category is a sub-category of the previous one is described by R. S. Ginzburg. She follows the theory of the American linguists J. Katz and J. Fodor involving the analysis of dictionary meanings into semantic markers and distinguishers but redefines it in a clear-cut way. The markers refer to features which the word has in common with other lexical items, whereas a distinguishes as the term implies, differentiates it from all other words. We borrow from R. S. Ginzburg her analysis of the word spinster. It runs as follows: spinster — noun, count noun, human, adult, female, who has never married. Parts of speech are the most inclusive categories pointing to major classes. So we shall call this component class seme (a term used by French semasiologists). As the grammatical function is predominant when we classify a word as a count noun it seems more logical to take this feature as a subdivision of a class seme. 1 Note the possibility of different graphical representation. 2 Componential analysis proper originates with the work of F.G. Lounsbury and W.H. Goodenough on kinship terms. 3 Prof. W. Haas (of Manchester University) delivered a series of lectures on the theory of meaning at the Pedagogical Institutes of Moscow and Leningrad in 1965. It may, on the other hand, be taken as a marker because it represents a sub-class within nouns, marks all nouns that can be counted, and differentiates them from all uncountable nouns. Human is the next marker which refers the word spinster to a sub-category of nouns denoting human beings (man, woman, etc. vs table, flower, etc.). Adult is another marker pointing at a specific subdivision of living beings into adult and not grown-up (man, woman vs boy, girl). Female is also a marker (woman, widow vs man, widower), it represents a whole class of adult human females. ‘Who has never married’ — is not a marker but a distinguisher, it differentiates the word spinster from other words which have other features in common (spinster vs widow, bride, etc.). The analysis shows that the dimensions of meaning may be regarded as semantic oppositions because the word’s meaning is reduced to its contrastive elements. The segmentation is continued as far as we can have markers needed for a group of words, and stops when a unique feature is reached. A very close resemblance to componential analysis is the method of logical definition by dividing a genus into species and species into subspecies indispensable to dictionary definitions. It is therefore but natural that lexicographic definitions lend themselves as suitable material for the analysis of lexical groups in terms of a finite set of semantic components. Consider the following definitions given in Hornby’s dictionary: cow— a full grown female of any animal of the ox family calf— the young of the cow The first definition contains all the elements we have previously obtained from proportional oppositions. The second is incomplete but we can substitute the missing elements from the previous definition. We can, consequently, agree with J. N. Karaulov and regard as semantic components (or semes) the notional words of the right hand side of a dictionary entry. It is possible to describe parts of the vocabulary by formalising these definitions and reducing them to some standard form according to a set of rules. The explanatory transformations thus obtained constitute an intersection of transformational and componential analysis. The result of this procedure applied to collective personal nouns may be illustrated by the following.

e. g. team → a group of people acting together in a game, piece of work, etc. Procedures briefly outlined above proved to be very efficient for certain problems and find an ever-widening application, providing us with a deeper insight into some aspects of language.1

Chapter 4 SEMANTIC CHANGE

Поиск по сайту: |

1 The problem was studied by W. Humboldt (1767-1835) who called the feature chosen as the basis of nomination— the inner form of the word.

1 The problem was studied by W. Humboldt (1767-1835) who called the feature chosen as the basis of nomination— the inner form of the word. 1 Nida E. Componential Analysis of Meaning. The Hague-Paris, Mouton 1975. P. 195.

1 Nida E. Componential Analysis of Meaning. The Hague-Paris, Mouton 1975. P. 195. 1 See the works by O.K. Seliverstova, J.N. Karaulov, E. Nida, D. Bolinger and others.

1 See the works by O.K. Seliverstova, J.N. Karaulov, E. Nida, D. Bolinger and others.

1 For further detail see: Арнольд И.В. Семантическая структура слова в современном английском языке и методика ее исследования. Л., 1966.

1 For further detail see: Арнольд И.В. Семантическая структура слова в современном английском языке и методика ее исследования. Л., 1966.